|

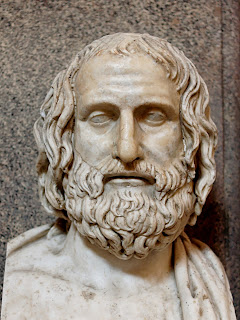

| Yeah. That's Euripides. Another odd bird of three. |

But, unlike the transition from poetry to fiction, the students are figuring out how to use another medium - what ends up on the page is as important as ever, but incidental to the thing we ultimately refer to as "theatre." It is a sister art of the two, and shares a lot -- economy, the power of the voice, image and music with poetry; it shares character, some structural components (conflict, plotting, climax), and Gardner's "vivid and continuous dream" with fiction. (That's from John Gardner's The Art of Fiction, a lovely cranky book young fiction writers should own!) But it remains the odd bird of the three.

But the kind of writing a play requires is often so different from the other two, it can feel to the first-timer, comfortable working on the page, as if I'd asked them to show up for their painting class only to find ballet shoes instead of easels.

Writing for movement; writing for any kind of performance is a sinewy request and begs the writer to imagine the world around the challenges the words present - every step of the way (pun intended). How do we understand the dynamic between two characters without bumbling into dull expository dialogue? How do we keep from over-writing when the language of the actors' bodies, or the movement of a prop, or even a lighting change tells us paragraphs of information? And most importantly, how do you trick yourself into writing action by action the content and heart of an idea?

You can't. You CAN'T - if you do it by yourself. You need to put your script down and watch actors move and speak your lines. You need to see the letter hidden in the plant to know if it makes sense there. You need to see actors improvise the moments you can't get right. You need to realize that the quick change doesn't work there, that the black out stops the action too much, that your character needs to change clothes before the next scene or it doesn't makes sense. You need a director or a designer to help you step back from the play to see the bigger shape it makes.

What makes it my favorite class of the year? I hand silly props (a plastic duck, an odd bird) to writers who have worked hard in their dorm rooms all semester, pair them up, and ask them to write something in ten minutes.

A: "Hold this."

B: "What is it?"

A: "Watch!"

B: "Will it hurt?"

A: "You'll see."

The ballet shoes suddenly make sense.

No comments:

Post a Comment